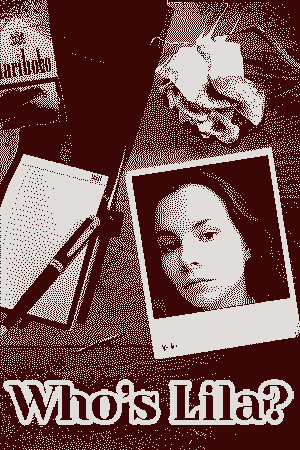

Developer: Garage Heathen

Release date: February 23. 2022

Price: 11.99$

Free Demo: Available

Supported platforms: Windows

Languages: English, Russian

Spanish, Simplified Chinese

Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1697700/Whos_Lila/?beta=0

Itch.io: https://garage-heathen.itch.io/whos-lila

Twitter: https://twitter.com/HeathenGarage

Description

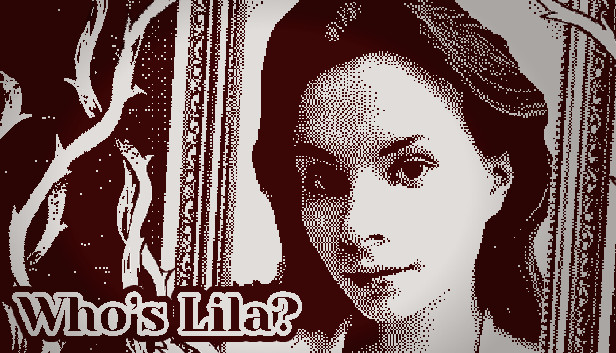

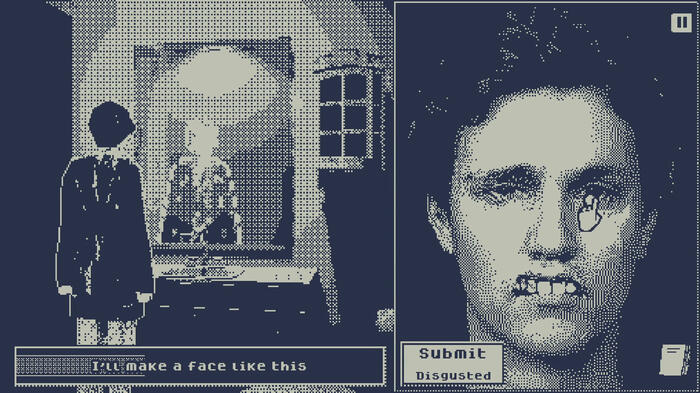

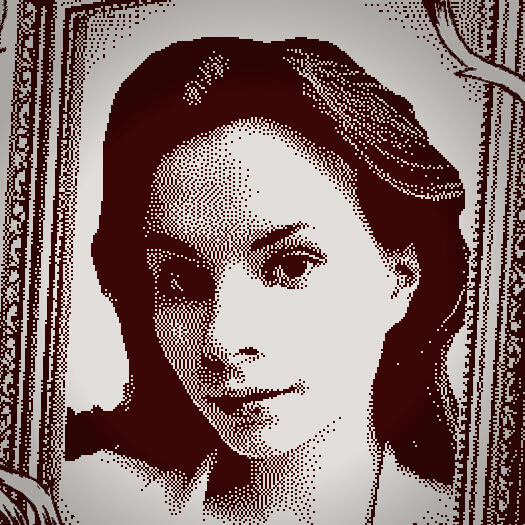

Who’s Lila? is a reverse-detective point-and-click adventure. It is an AI-powered choice-driven game, where instead of choosing dialogue options, you have full control over the character’s face.

Will you solve the enigmatic mystery? Will you be able to tackle your own emotions in pursuit of your mysterious goals?

And finally, will you find the answer to the ultimate question – Who is Lila?

Features

- Neural network-powered emotion detection

- 15 endings and choice-driven gameplay

- Steam achievements

- Ditherpunk visual style

- 50+ unique soundtrack pieces written specifically for the game

- 6+ hours of gameplay

- Unlockable palettes

- And more..

This is a critical analysis, not a review, of the game Who’s Lila? As such, there are spoilers ahead. I would strongly recommend playing the game to completion before reading.

On Tulpamancy as Aesthetic Ontology in Who’s Lila?

Who’s Lila is a 2021 video game developed by the Russian independent game studio Garage Heathen. It describes itself as a “reverse detective game,” but it is much more nuanced than simply that. The central gameplay mechanic centers around the manipulation of William’s face to express emotions as he is investigated for the murder of Tanya Kennedy. This simple narrative and the mechanics of the game themselves begin to break down through the intertextual, thematic, and augmented reality elements of the game. The central question of the work (Who is Lila?) becomes both the guiding narrative arc and the interpretive model for the game. Derrida’s 1972 text Dissemination creates a theory where reading and writing are bound and equivocated by deconstructing Plato’s Phaedrus. Derrida will later expand this theory of deconstruction to be what he calls a hauntology, that is, an ontology of ghosts. The construction of Lila and the aesthetic ontology as tulpamancy creates and plays with how Derrida’s deconstruction/hauntology defines a text.

Garage Heathen plays with aesthetic form in order to defer meaning and narrative authority in a Derridean way. In 0-The Fool, II-The High Priestess, and XII-The Hanged Man, the game defers narrative authority. The construction of the user interface up to this point—that is, with two thirds of the screen dedicated to moving across a scene with a fixed camera angle, and the other third dedicated to a face—begins to break down. Lila’s face is revealed to be a projection, and when the player, now in a first person perspective, steps away from this projection, there is a projector. The player has three choices here which correspond to three endings: remove Lila’s projector reel and leave the projector without any reel (Garage Heathen 0-The Fool); leave Lila’s projector reel on the projector (Garage Heathen II-The High Priestess); or replace Lila’s projector reel with William’s projector reel (Garage Heathen XII-The Hanged Man). This play with form defers the assumed narrative authority that exists within the image of the face. As such, there is another layer added to the rhetoric of the face-manipulation mechanic; that is to say, not only is the face a construct in that it is a deliberate manipulation of the face, but it is also a construct of the projector. Derrida defines the visor effect as the fact that “we do not see who looks at us… To feel ourselves seen by a look which it will always be impossible to cross… to signify that someone, beneath the armor, can safely see without being seen” (Derrida Specters 6-9). Here, the game utilises this visor effect to defer narrative authority and to call into question character identity. On a narrative level, this unstable identity already existed, but with this move, unstable identity is founded on a formal level. It does so by breaking down the relation between the signified and the signifier. No longer can the right side of the screen be understood to be merely a strict representative of facial expressions; instead, it enters into an unstable symbolic order. This is further complicated in HERE ARE THE WORds OF PROF. F. I. RYIBKIN [sic], an external website linked in V-The Hierophant, Ryibkin describes how “THE PRINCE was gradually fooled into thinking he was looking in a mirror. And when he saw his reflection dance a certain way, he would occasionally think it would be fun to dance the same way.” This is complicating in two ways: first, on the narrative level, it troubles the notions of perspective and character; secondly, on the level of form, it defers the meaning of the term “text” itself. That is to say, this website, and the PDF file which it links to, are “outside” the game. However, they are not something akin to a guidebook or an intertextual source, rather, they must be engaged with in order to progress within the game. As such, these documents trouble the notion of “text.” The link to HERE ARE THE WORds OF PROF. F. I. RYIBKIN is found while playing the game, then, at the bottom of the website, there is a link to another website with the text “The password may not be revealed openly, but the DAEMON knows it. Look at ANSWER.txt. Base Folder.” which means you must go into the game files to find the password to unlock another website. Upon unlocking this you download a PDF file which, among more information, gives another password for a computer within a game.

The game sets up its own interpretive model and vicarious reader through the character of Detective Yu.

The game sets up its own interpretive model and vicarious reader through the character of Detective Yu. You meet Yu for the first time whenever William is interrogated for the first time. After meeting him, a new save file is created, when you load this save file, Yu invites you to discuss Tarot cards with him. These Tarot cards are awarded to you for each ending you complete. As such, after each ending, the text begins to interpret itself. In II-The High Priestess-Yu, Lila directly asks Yu to respond to various interpretations of who she is. She says:

“I am Will’s tulpa. He’s made me after the passing of his mother to.. Oh wait-wait. No, I’m the vengeful spirit of the girl named Tanya Kennedy and.. Oh, no, wait. I’m a scientific experiment conducted by the US government to brainwash its citizens to… Or am I a metaphor for mental abuse everybody has seen about a hundred times already? Or am I a twisted incarnation of Will’s dark tormented psyche? ooh.. Which one is it, detective?” (Garage Heathen II-The High Priestess-Yu—ellipses are not mine)

As Yu notes, Lila is being playful here, mocking these interpretations and interrupting them with other interpretations. As such, in Lila’s playing, and in fact in the rest of the game, meaning is always deferred.

As such, in Lila’s playing, and in fact in the rest of the game, meaning is always deferred.

The game sets up an aesthetic ontology which, by necessity, acts as a guide to interpret the game. In VIII-Strength-Yu, Lila explicitly invokes Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Garden of Forking Paths” as a way to explain both the ontology of the game world as well as the ontology of interpretation. Whereas Yu thinks he “get[s] it, [that] the story could’ve unravelled in many different ways and so on… But [he wonders] which one of them actually happened?” Lila tells him that in fact he doesn’t “get it. They all happened… All of them [the endings] are [canonical]. And none of them are.” (Garage Heathen VIII-Strenth-Yu). She further states “You seem to think that some of the dreams you see are more important than others, detective. I suggest you reconsider. All of them are equally ephemeral. All of them are nothing but dreams.” (Garage Heathen VIII-Strength-Yu) This, by its very nature, evokes multiple readings, all of which must be canonical and non-canonical. This works on a narrative, thematic, and aesthetic level. In the narrative sense, all the contradictory events of the story all happen at once. On a thematic level, this deals as well with the themes of identity. On an aesthetic level, this instructs us that all the readings that Tanya offers playfully in II-The High Priestess-Yu, as well as any other readings, both are and are not true.

This aesthetic ontology is further complicated by XX-Judgement-Yu. Not only does every path “exist simultaneously, intersecting” but, Yu notes, “In a weird way, They seem to dictate each other’s logic too.” (Garage Heathen XX-Judgement-Yu). After this, Yu further says that he is “not sure if [he] can grasp the picture in it’s [sic] entirety yet” (Garage Heathen XX-Judgement-Yu). This dramatizes Derrida’s metaphor of the text as a textile: that “There is always a surprise in store for the anatomy or physiology of any criticism that might think it has mastered the game, surveyed all the threads at once” (Derrida Dissemination 1608). Yu, as vicarious reader, fundamentally can not grasp the picture in its entirety. Further, he doesn’t “think [he]’ll be able to find satisfaction until [he] understand[s] each little thing… [he] feel[s] it’s what [he] need[s] to do in order to find out who [Lila is]” (Garage Heathen XX-Judgement-Yu). Yu thus represents that urge in the reader to trace every thread, “to look at the text without touching it” (Derrida Dissemination 1608). We know that Yu has been “watching [Lila] intently… From the point William woke up in his apartment / Right until the end.” (Garage Heathen XI-Justice-Yu). That is, from the beginning of each ending to the end of each ending. To be clear, Yu, perhaps falsely, marks a border of the textuality. That what is to be understood is within those parameters, perhaps permitting the Yu conversations. However, the text, both in a Derridean sense and literally, encompasses more than that.

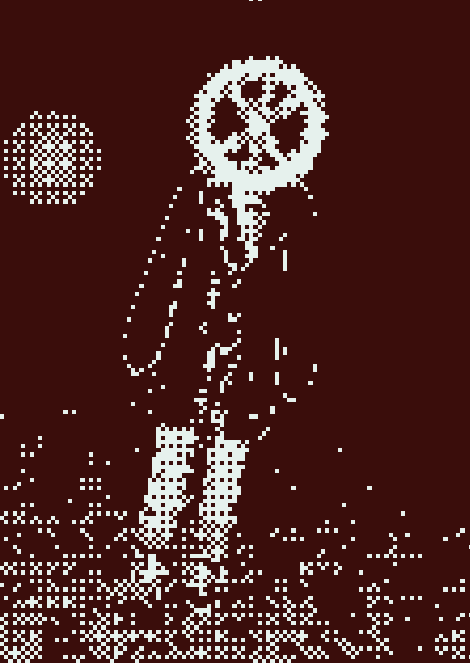

The character Wheeliam serves as another interpretive model within the game.

The character Wheeliam serves as another interpretive model within the game. To talk to Wheeliam you must intentionally corrupt a save file. After doing so, you load the corrupted save file and the DAEMON will give you coordinates to walk to. At those coordinates you find Wheeliam and he says you may ask one question, which, for the only time in the game, you must type. There are ten valid questions which can be asked. These questions are not incidental, but rather can be found on the background image of a store page. Four of these questions are fundamental to the aesthetic ontology of the game: “Who’s Detective Yu?”; “1899?”; “Who’s Lila?”; and “What for?” (Garage Heathen Wheeliam). It is here we get some of the straightest, yet most unsatisfactory, answers to the central question of the text. Both the question of “Who’s Detective Yu?” and “1899?” corroborate the reading of Detective Yu as a surrogate reader. “Who’s Detective Yu?” is answered with “Your mind is a detective in ways.” Though this is not merely a connection between you and Yu, it instead enforces the ontological connection of reading and writing as being one in the same through its connection to genre. Derrida explain that “One must then, in a single gesture, but doubled, read and write.” (Derrida Dissemination 1608). That is to say, that the act of interpretation is both reading and writing. However, one should be careful not to just “add any old thing” or they risk adding nothing, and on the other end, one who “would refrain from committing anything of himself, would not read at all” (Derrida Dissemination 1608). As such, by casting the player as “a detective in ways,” the game is encouraging a Derridean reading/writing of the text. To follow Derrida’s textile metaphor, just as the reader of the text weaves “the hidden thread” (Derrida Dissemination 1608) of the text, so too does the detective read/write the story via linking threads on a “conspiracy board.”

Wheeliam also contributes to a reading of the titular questions of Who’s Lila? When asked who Lila is, Wheeliam tells us “Lila is the mystery of not knowing who Lila is.” (Garage Heathen Wheeliam). This answer is corroborated by /YuEndPart2/—a seemingly glitched part of the game, where it says that Debug.Log says “Warning! Missing header at /YuEndPart2/” which is actually a secret text in the game files—that enforces that Lila is “not a tulpa, not the mother of UIW-AM / Not even Lilith or an archetype” (Garage Heathen /YuEndPart2/) but, yet she is “all those things / [and she is] the mystery of not knowing who Lila is.” She says the her “nature is exactly this” this being the text, the game, and that she is “all this” (Garage Heathen /YuEndPart2/). As such, since Lila is the text, the text is “designed in away that makes me just about explainable / But at the end of the day [it is] no more than a simple question: / Who is Lila?” (Garage Heathen /YuEndPart2/). Then, when one asks Wheeliam “What for?” he responds

“Indeed, why even bother, if she isn’t more than the question itself? was all you found in vain? I do not think so, as the flowers are born to wither so is the imaginary machine that’s being built only to completely obliterate itself. fleeting beauty…” (Garage Heathen Wheeliam).

Wheeliam thus assigns an aesthetic value to the interpretation. That even though the answer is no more than the question, that there is an aesthetic value in the interpretive process nevertheless. In Specters of Marx, Derrida says of the specter that

“It is something that one does not know, precisely, and one does not know if precisely it is, if it exists, if it responds to a name and corresponds to an essence. One does know: not out of ignorance, but because this non-object, this non-present present, this being-there of an absent or departed one no longer belongs to knowledge. At least no longer to that which one thinks one knows by the name of knowledge.” (Derrida, Specters, 5)

In Specters of Marx, Derrida is expounding upon his theory of deconstruction which he claims has, all along, been a theory of hauntology. That is to say, that deconstruction is a study of ghostly traces. Lila, as a narrative character and as a representation of aesthetic ontology is this exact sort of specter. In other words, the text itself is a spectral being.

Lila, as a narrative character and as a representation of aesthetic ontology is this exact sort of specter. In other words, the text itself is a spectral being.

My central claim is that Lila’s aesthetic ontology is that of Tulpamancy. Tulpamancy is an idea adapted from Buddhist tradition and adapted into Theosophism, but that notion is not exactly what the game nor I mean by Tulpamancy. Lila, in some way, feeds off of or exists in conscious experience. The game is not clear about how exactly this is, it offers various interpretations—from mass brainwashing by the FBI, to spiritual constructions, to memes, to Jungian collective unconscious archetypes—that Lila rejects and simultaneously affirms. What actually happened on a narrative level is perhaps another paper altogether; what is important to note here is how this plays into Derridean philosophy. That is, Lila exists only insofar as she is consciously engaged with. Lila cannot merely be read, she must be written as well. Her “nature is exactly this. / [She is] all this… [and] As long as the one playing this game doesn’t understand what [she is] / [She] will remain alive in their mind” (Garage Heathen /YuEndPart2/). As such, this essay functions to engage with the central question, “the mystery itself,” that Lila is, and, in so doing, keeps Lila alive. Lila is not Lila just as “a text is not a text unless it hides from the first comer, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of its game.” (Derrida Disseminations 1608). Both Lila and “a text remains, moreover, forever imperceptible.” (Derrida Disseminations 1608).

Both Lila and “a text remains, moreover, forever imperceptible.” (Derrida Disseminations 1608).

Who’s Lila? dramatises the Derridean interpretive model on both a narrative and a formal level. That is to say, through deconstructing and deferring narrative authority, Garage Heathen creates an aesthetic ontology which can be described equally as tulpamancy, deconstruction, or hauntology. Derrida’s texts Dissemination and Specters of Marx can thus be read alongside Who’s Lila? To understand how texts function across mediums and, in similar but distinct ways, become all-encompassing textualities. To ask the question Who’s Lila? One is asking the fundamental Derridean interpretive question.

To ask the question Who’s Lila? One is asking the fundamental Derridean interpretive question.

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques. “Dissemination.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Critcism, edited by Vincent B. Leitch, 3rd ed., Norton and Co., 2018 1602-36

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge 2006.

Who’s Lila?. Garage Heathen, 2021. https://store.steampowered.com/app/1697700/Whos_Lila/?beta=0